This article was inspired by a comment recently made by a reader of a past article, in which I referenced the “Masters” of classical horsemanship from a few centuries ago.

“What I want to question is why the halo over the classical masters? Why do we hold them as the benchmark? We have representations of their work (writings and paintings) but no moving video. I’m not saying they aren’t who we think they are, or that I disagree with their principles, just questioning where we get our baselines from in such an arbitrary activity as sitting on the back of animal for human pleasure. Are we just romanticizing a historical era we see as particularly artistic? Every time someone says ‘well the classical masters said…’, we should be just as critical as if they had said ‘well the natural horsemanship people say…’ or ‘Olympics medalists say…’”

I thought this was a great question and observation and I feel a complete answer is called for, so…

Why do some of us modern trainers so revere the classical masters?

Let me begin by saying that I believe the dogmatic following of the teachings of any trainer, historic or modern, is misguided. We must certainly view every training method with a critical eye and I don’t think I have met a single practitioner of “classical” horsemanship that ever suggested otherwise.

I am fairly certain that in their time the followers of one “master” or another may have been as religiously devoted to just them as so many followers of today’s famous clinicians, that is by no means what I am suggesting when I quote one master or other.

The passage of time has allowed the works of the masters of the “old world” to be tested and retested for many generations by equestrian scholars dedicated to perfecting the art of horsemanship. These men were typically not following the dogma of any one personality, but were instead putting these methods to practical testing through the training of warhorses; there simply is no better crucible by which to burn away flawed or faulty practices.

Let me quickly add that there was not, and is not, a monolithic truth in “Classical Horsemanship”. While there are accepted goals that transcend the centuries and regional differences, the actual methods of the Masters of Horsemanship varied wildly between individuals and time periods. One can read the works of a French trainer and those of his German contemporaries and find them diametrically opposed in their views of “correct” horse training methods, even to the point of calling out one another by name as inferior horsemen.

One can also read the works of a single master at different points in his life and find him specifically contradicting his earlier works in later writings. More often, however, you will find one master referring back to the teachings of the particular horsemen whose work inspired their own training methods.

The result of all this diversity and evolution of horsemanship was the formation of differing “schools” of classical riding, each labeled as Classical Horsemanship, and rightly so. The German Classical School is just as “Classical” as the French Classical Method, even though they differ in how they each go about trying to achieve similar goals. The reason there is such debate today as to what constitutes “correct” or “real” classical horsemanship is that throughout the classical period (and just how long the classical period was is also a point of debate), the acknowledged masters did not always agree as to what was correct.

But all is not chaos. There are lines of practice from Master to Student, with each subsequent generation striving to improve on the works of their instructors. Each new Master would spend his career training horses for battle while teaching Kings, Princes, and Nobles the art of horsemanship. All of this was at a time when the skill of the rider, along with the training and ability of the horse, literally meant the difference between life and death on the battlefield. These scholars studied horsemanship in a way that’s just not practical today. We must recall that horsemanship was not a hobby or sport for these men, but a way of life.

It’s important to remember that before the time of the French Revolution, horsemanship was taught in Universities alongside mathematics and literature. After that, further instruction by way of standard military service. For these men, the art of horsemanship was the quest for perfection, not for a perfect score. They sought to impress their comrades in arms, commanders, sovereigns as well as their foes—not the arbitrary whims of judges. After all, the riders they pitted their skills against were very often attempting to kill them.

The horses these men worked with were carefully bred for specific conformation and temperament. It took years to raise and train, representing a huge investment in time and money. Their continued well-being and soundness were of paramount importance. Everything about classical horsemanship was aimed at maximizing the abilities and usefulness of the horse while at the same time, giving it the longest possible useful life span. Compare that to today, when even great horses seem disposable and the push to get them into competition as soon as possible is so intense.

So while the precise methods and techniques used might differ from one to another, the goals of most of the classical masters were very similar:

- A willing, courageous, and confident horse that put all of its energy at the rider’s disposal and that could be ridden with the lightest of aids.

- A horse that was balanced to the hind, physically developed and conditioned to allow for all the maximum engagement and collection that conformation allowed. In other words, a horse that displayed the same athleticism under saddle as it did as a young horse at play in the pasture.

- A horse that would maintain all the above while staying sound for a very long life of service.

Notice that I did not mention the purpose for which the horse is being trained as part of the goals. In my understanding of classical horsemanship the use of the horse is not important. A horse trained to its physical and emotional potential will perform as well as its conformation and breeding allow, regardless of the activity, unless the very nature of the activity runs contrary to these cornerstone principles.

(wikipedia)

So to answer the original question more succinctly—we look to the wisdom of the classical masters if our goals match the cornerstone principles they held paramount. Their methods are the results of generations of academically trained horsemen seeking to perfect the art of horsemanship for its own sake (as well as for purposes we agree with), while the motivation and goals of most Olympians and Natural Horsemanship clinicians are not. For the modern master horsemen and women whose goals and methods parallel classical teachings, most of them read and revere the work of the classical masters as well.

We should study the works of the classical masters and strive to understand them. We should work to apply their teaching in our own riding, observe and assess their effectiveness, discard that which does not ring true to us, and take that which does and incorporate it into our own quest for perfection.

Below is my personal reading list of classical horsemanship:

- Xenophone, The Art of the Horse, (2006) unabridged republication of the edition published by Little, Brown and Co. 1893

- Le Maneige Royal – Antoine de Pluvinel English Translation of the 1629 work

- A General System of Horsemanship – William Cavendish – 1743

- School of Horsemanship – Francios Robichon de la Gueriniere – English translation first published in 1733 as Ecole de Cavalerie

- The Gymnasium of the Horse – Gustav Steinbrecht – English translation of the late 19th Century work

- Méthode d’équitation basée sur de nouveaux principes, (Method of riding based on new principles), François Baucher, 1842

- H. Dv. 12 German Cavalry Manual: On the Training Horse and Rider, 1937 – Recently translated into English

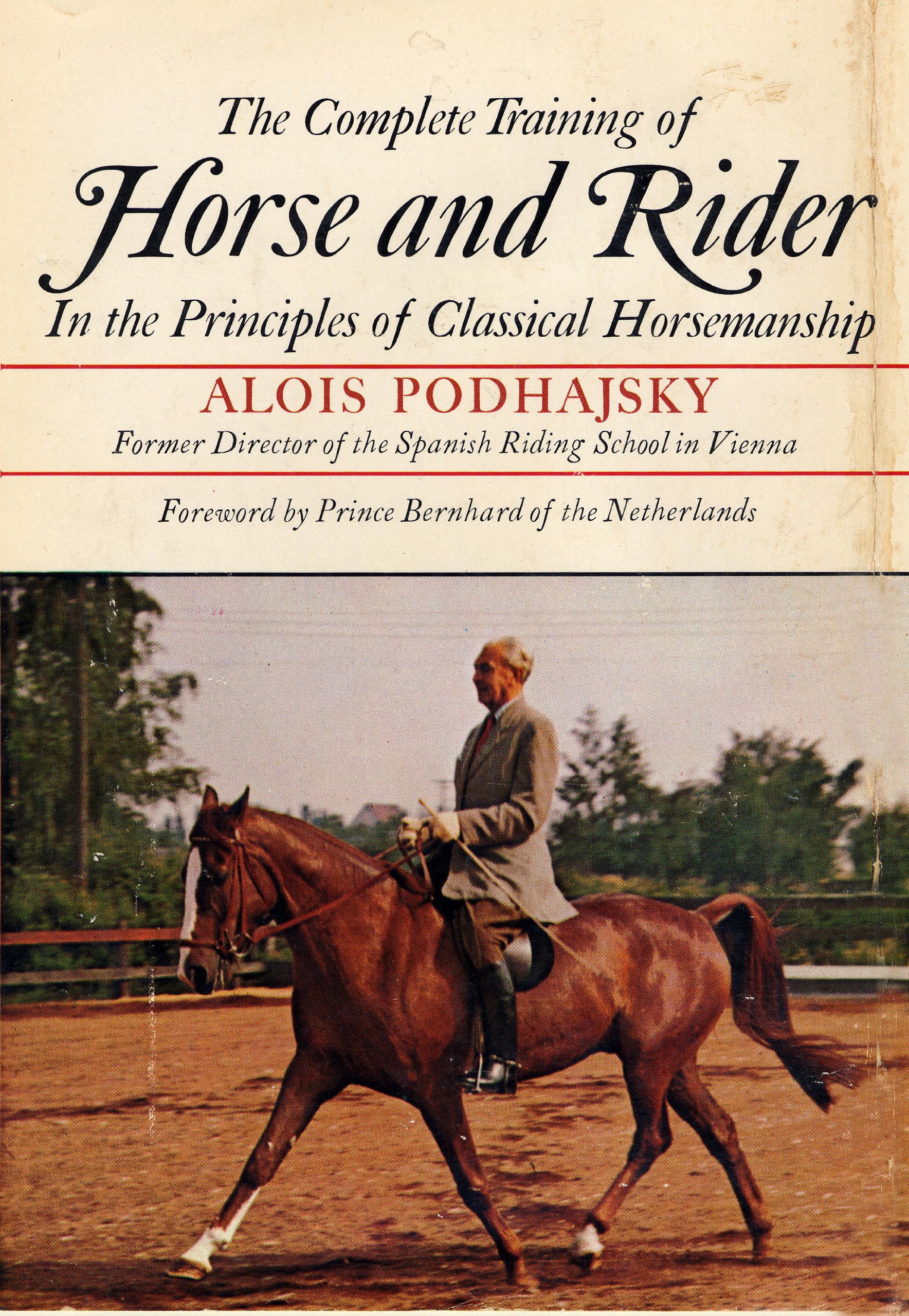

- The Complete Training of Horse and Rider in the Principles of Classical Horsemanship – Alois Podhajsky – 1967