Our horses see the world very differently from us in many ways. These differences, due to the structure and placement of their eyes, have profound influences on how they react to visual stimuli and should be thoughtfully considered during their training and indeed in all aspects of horsemanship. These differences include the field of view, color perception, light adjustment, motion detection, acuity, and much more. In this article I hope to detail some of the differences and how they relate to training, riding, and caring for horses.

Our horses see the world very differently from us in many ways. These differences, due to the structure and placement of their eyes, have profound influences on how they react to visual stimuli and should be thoughtfully considered during their training and indeed in all aspects of horsemanship. These differences include the field of view, color perception, light adjustment, motion detection, acuity, and much more. In this article I hope to detail some of the differences and how they relate to training, riding, and caring for horses.

Field of view

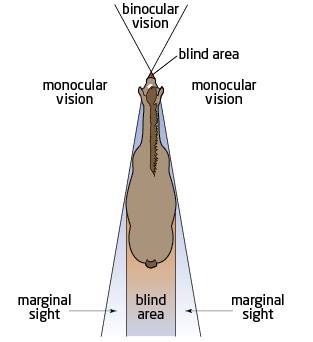

The horse’s eye is the largest of all land mammals and its location gives the animal a nearly 360° field of view; that is ‘nearly’ 360°. The horse cannot see directly in front of themselves for a short distance, nor directly behind themselves unless they move their head. This is why we are all taught never to approach a new horse from either of these directions and to always make them aware of our location as we pass behind them. It is important to note that even though the horse can see in nearly a complete circle, only about 20% of that vision is binocular, the remaining 80% is monocular vision. This means that most of the field of view is seen by only one eye. This explains why your horse will try to swing his head to the side or even turn his body, to look at something that has ‘caught an eye’. This is why it is so important that we earn the trust and respect of our horses in order to have them able to concentrate on the work we ask of them and not go casting about with their gaze in order to bring things into full view and enable depth perception.

One of the interesting things about the monocular peripheral vision of the horse is that he is capable of seeing out of both eyes simultaneously and separately. This is in part due to the limited corpus calossum development in the horse’s brain. The corpus calossum serves to transfer information from one side of the brain to the other and without good transfer, the two sides are left to operate essentially independently of each other. The advantage this gives the horse is that it can effectively look in two directions at once. The disadvantage is that something seen out of one eye, may not be recognized when seen again out of the other. This is why your horse may treat something as new and scary when passing it on the right side when it has already passed it on the left side several times without fear.

One of the interesting things about the monocular peripheral vision of the horse is that he is capable of seeing out of both eyes simultaneously and separately. This is in part due to the limited corpus calossum development in the horse’s brain. The corpus calossum serves to transfer information from one side of the brain to the other and without good transfer, the two sides are left to operate essentially independently of each other. The advantage this gives the horse is that it can effectively look in two directions at once. The disadvantage is that something seen out of one eye, may not be recognized when seen again out of the other. This is why your horse may treat something as new and scary when passing it on the right side when it has already passed it on the left side several times without fear.

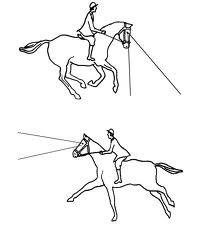

Another vital aspect of the horse’s field of view is that though it has binocular vision for about a 65-degree arc, this arc is actually rather narrow vertically. Consequently, the horse needs to lift its head to focus its vision on objects at a distance and lower its head to see something on the ground in front of them. This is why the horse will lift its nose as its speed of travel increases, looking further ahead in order to have the time to adjust to changing conditions and obstacles in its path. You may notice that jumpers and cross-country riders always allow the horse to ‘have its head’ on the approach to enable it to look at the approaching jump and even with this, the last stride of the jump is being done blind by the horse.

A horse ridden ‘on the bit’ or ‘on the vertical’ can only see a limited distance in front of them and should not be expected to maintain this headset for faster work; which also means a horse ridden behind the vertical or with its head very low, is effectively blind to anything beyond a very short distance ahead. Is it surprising that we sometimes witness highly trained dressage mounts suddenly blowing up and having a panic attack during tests?

A horse ridden ‘on the bit’ or ‘on the vertical’ can only see a limited distance in front of them and should not be expected to maintain this headset for faster work; which also means a horse ridden behind the vertical or with its head very low, is effectively blind to anything beyond a very short distance ahead. Is it surprising that we sometimes witness highly trained dressage mounts suddenly blowing up and having a panic attack during tests?

This may also explain why horses are generally more willing to relax their poll, thus allowing the head to fall onto the vertical while working on a circle. While moving in a circle they are looking only a short distance ahead as compared to when they are working along the wall. There are obviously other factors at work when schooling the horse on the circle, but the horse’s field of view should be considered along with them.

I feel it is important that we not ask a horse to maintain a vertical head position for extended periods of time but rather to break them up with frequent periods of freedom to lift their heads and have a look around.

Color Vision

A lot of people believe horses are unable to see color, but research indicates this is not the case. It is true they are not able to see color as distinctly as we do, however, they do see the world in color. Painting jumps standards strongly contrasting colors has been done for many years for the very reason they it helps the horse distinguish them from the background of the arena. There is evidence to indicate that horses have a degree of color blindness, but this does not mean they cannot see any color, it only means they might perceive the color red, much the same way as a human with red/green color blindness. So if you wish the paint your arena elements to help your horse see them better, white and blue would be more useful than red and green.

A lot of people believe horses are unable to see color, but research indicates this is not the case. It is true they are not able to see color as distinctly as we do, however, they do see the world in color. Painting jumps standards strongly contrasting colors has been done for many years for the very reason they it helps the horse distinguish them from the background of the arena. There is evidence to indicate that horses have a degree of color blindness, but this does not mean they cannot see any color, it only means they might perceive the color red, much the same way as a human with red/green color blindness. So if you wish the paint your arena elements to help your horse see them better, white and blue would be more useful than red and green.

Light Adjustment

Horses are far better adapted to see in low-light situations than we are. They can perceive objects in light levels so low as to be essentially pitch black to us. What they cannot do as well as us is adjust to rapidly changing light levels. This is why they will stand for several moments blinking blindly when a light is turned on in a dark barn. It also explains why a horse might balk at entering the shadowed end of an area or refuse to step into a dark trailer on a sunny day. This is something we must be cognizant of in all our dealings with horses, just because you are able to look into a dark place and see that it is perfectly safe, does not mean your horse can.

Motion Detection

Horses are highly sensitive when it comes to spotting motion. When unexpected motion is detected in the peripheral vision, which has poor acuity, the horse’s first instinct is not to turn and look at it with both eyes, bring it into focus, and determine what it is and how far away; its first instinct is to run to an absolutely safe distance, then turn and look. Have you ever noticed how nervous your horse gets when riding outdoors on windy days? It is because EVERYTHING is moving and he cannot determine what is a threat from what is not.

Here again, I must reiterate how important it is that you have your horse’s trust and respect and by this, I do NOT mean your horse should be more afraid of disobeying your command than it is of that thing moving over in the bushes. I am saying your horse should have come to respect your judgment and worthiness as a leader and trust you to protect him so if you do not think it is worth getting scared about, he won’t concern himself with it.

Obviously, this could be a topic for another article or even a whole book but suffice it to say that one of the main factors that you will want to keep in mind is the ‘connection’ to the horse. By connection, I mean riding in presence, being aware of your horse, and making him aware of you, through the aids at all times. I am not talking about micromanaging every motion of the horse. What I am suggesting is that by keeping the seat independent, moving with the horse, the hands light and rein aids flexible, and keeping your legs lightly touching the horse’s side at all times, you can maintain mutual communication with your horse. By doing so, you will become aware right away when he is startled by some movement or sound and is instinctively reacting with flight. This way you can respond more quickly to counter this reaction with a calm firming of the aids for just a moment; in other words catching the spook before it becomes a run and assuring the horse that you are right there with him, protecting him and that he has nothing to fear.

Visual Acuity

I mentioned the acuity of the peripheral vision in a previous section, now let’s address it more completely.

In general, the horse has slightly less visual acuity than we do, though still better than a lot of other animals we are familiar with; cats or dogs for instance see with less acuity than horses. Horses may have an advantage over us when it comes to seeing at great distances, but in the middle distance and up close, they are weaker. It is very important however that we remember factors specific to the horse’s acuity.

First, due to a linear area of the eye where the concentration of ganglion cells is very high, there is formed a “visual streak” where acuity is radically higher than outside this area. This ‘streak’, along with the placement of the eyes on the skull is what creates the narrow field of focus for the horse, as I discussed earlier.

The other aspect we must keep in mind about the horse’s visual acuity is that the horse changes focus MUCH slower than we do. Our eyes have evolved to be able to almost instantly change focus when we shift our gaze from near to far or vice versa, however, the horse’s eyes take much longer by comparison. When we spot something moving out of the corner of our eye ‘over there’ and glance over to see what it is, we can very quickly determine what it is, if it is moving at us, and whether or not it is a threat, then go on about our ride. because the horse is simply not able to do this, so we must be cognizant of the fact and consider it as we train or ride.

Conclusion

I will wrap up this article by suggesting that as responsible horse owners, it is incumbent on us to be aware of, and take into consideration, how differently our horse perceives his world from how we see it.

When we find ourselves thinking “What has gotten into this horse, what does he see, there is nothing over there?” it would serve our best interests, as well as those of the horse, to remember that what he is seeing may be very different from what we are seeing.

It is also vital to keep in mind how the frame we are asking the horse to adopt affects how and what he can see. Consider for a moment, how calm you would be if someone blindfolded you and asked you to run an obstacle course.

<p”>We ask a great deal from our equine partners by way of trust and obedience. It is up to us to be sure we are deserving of this trust by not asking that it be blind.